FastMCP is a fantastic library. It abstracts away the gnarly bits of the Model Context Protocol and lets you write MCP tools with clean, Pythonic code. Dataclasses work beautifully as return types. Pydantic handles the serialization. Everything just works.

Until it doesn't.

New Framework, Who Dis?

I was building MCP tools for Azure DevOps integration when I discovered something interesting: FastMCP has a subtle asymmetry in how it handles dataclasses. It'll happily serialize your dataclass outputs to JSON for clients, but it won't deserialize JSON inputs back into your dataclass parameters.

This cost me several hours of debugging, a comprehensive RCA document, and one blog post about testing the wrong layer (see: Why Your Tests Passed But Your API Failed).

Let me save you the same journey.

What's the Problem?

Here's the trap. This code looks perfectly reasonable:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from fastmcp import FastMCP

@dataclass

class AzureDevOpsPRContext:

organization: str

project: str

repository: str

pr_id: int

mcp = FastMCP("Azure DevOps Tools")

@mcp.tool()

async def analyze_pr_comments(

pr_context: AzureDevOpsPRContext,

) -> list[str]:

"""Analyze comments on a PR"""

# This works fine when called from Python

org = pr_context.organization

return [f"Analyzing {org}..."]

In Python: ✅ Works perfectly

Via MCP protocol (Copilot, Claude, etc.): ❌ Crashes with AttributeError: 'dict' object has no attribute 'organization'

But Pydantic Should Handle This, Right?

This is where it gets interesting. If you dig into FastMCP's code, you'll find it uses Pydantic's create_model() to generate JSON schemas. And Pydantic can handle dataclasses! Watch:

from pydantic import create_model

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class MyData:

value: str

# Pydantic can totally deserialize this

DynamicModel = create_model('DynamicModel', value=(str, ...))

instance = DynamicModel(value="test")

print(instance.value) # Works!

# It even handles dataclass fields

from pydantic.dataclasses import dataclass as pydantic_dataclass

result = pydantic_dataclass(MyData)

obj = result(**{"value": "test"}) # Also works!

So why doesn't it work in FastMCP?

Here's What Actually Happens

FastMCP has built-in serialization support for outputs:

# In FastMCP's codebase (simplified)

def _create_model_from_class(cls):

"""Convert a dataclass to a Pydantic model for OUTPUT"""

# This works beautifully

fields = {

field.name: (field.type, ...)

for field in dataclasses.fields(cls)

}

return create_model(cls.__name__, **fields)

This lets you return dataclasses and FastMCP serializes them to JSON automatically. Perfect!

But for inputs? FastMCP gets JSON from the MCP client, deserializes it to a Python dict using standard JSON parsing, and passes that dict directly to your function. No dataclass reconstruction. No Pydantic magic. Just a dict pretending to be your dataclass.

The asymmetry:

OUTPUTS (works):

Your dataclass → FastMCP's _create_model_from_class() → Pydantic model → JSON ✅

INPUTS (doesn't work):

JSON → FastMCP's JSON parser → dict → Your function expecting dataclass ❌

You Have Yet to Convince Me, Sir!

"But Jack," you're thinking, "why would they do this? Surely they'd implement both directions if they implemented one?"

Fair question. Here's my theory: MCP is a language-agnostic protocol. It's JSON-RPC at its core, designed to work with any language. The protocol requires JSON-compatible types as inputs—strings, numbers, booleans, arrays, objects (dicts).

FastMCP could theoretically reconstruct your dataclasses from the incoming JSON, but that would be a Python-specific convenience feature. The framework chose to stay closer to the protocol specification: JSON in, JSON-compatible outputs.

The problem? Python developers see dataclasses work as return types and assume they work everywhere. The framework doesn't explicitly prevent you from using them as parameters—your type hints are valid Python, your tests pass—but the production deployment path tells a different story.

The Wrong Fix (Don't Do This)

My first instinct was to wrap the conversion myself:

@mcp.tool()

async def analyze_pr_comments(

pr_context: dict, # Surrender to the dict

) -> list[str]:

# Manually reconstruct the dataclass

context = AzureDevOpsPRContext(**pr_context)

org = context.organization

return [f"Analyzing {org}..."]

This works, but now you've lost your type hints for the input. Your IDE won't help you. Clients won't know what fields are required. The generated JSON schema will just say "object" instead of specifying the structure.

You've made the API work but sacrificed discoverability.

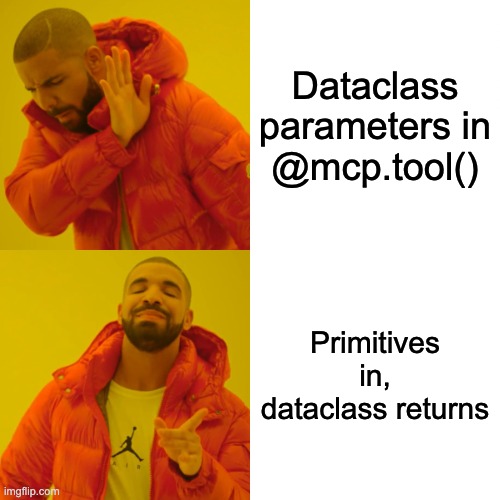

The Right Fix: Primitives In, Complex Out

Here's the pattern that actually works with FastMCP:

@dataclass

class AzureDevOpsPRContext:

organization: str

project: str

repository: str

pr_id: int

@mcp.tool()

async def analyze_pr_comments(

organization: str,

project: str,

repository: str,

pr_id: int,

) -> AzureDevOpsPRContext: # Dataclass as OUTPUT ✅

"""Analyze comments on a PR"""

# Construct your dataclass internally

context = AzureDevOpsPRContext(

organization=organization,

project=project,

repository=repository,

pr_id=pr_id

)

# Do your work with the nice dataclass

analyze_comments(context)

# Return it - FastMCP serializes it beautifully

return context

Or even better, use a single primitive that encodes what you need:

@mcp.tool()

async def analyze_pr_comments(

pr_url: str, # "https://dev.azure.com/org/project/_git/repo/pullrequest/123"

) -> AzureDevOpsPRContext:

"""Analyze comments on a PR"""

# Parse the URL and construct your dataclass internally

context = parse_pr_url(pr_url)

analyze_comments(context)

return context

The pattern: Accept primitives (str, int, bool, list[str], dict) at the API boundary. Construct your complex types internally where you control the instantiation. Return complex types freely—FastMCP handles that direction perfectly.

Why This Matters

This isn't just a FastMCP quirk—it's a reminder about API boundaries. When you cross serialization boundaries, type assumptions break. JSON doesn't have dataclasses. It has objects (dicts). The framework can't magically reconstruct your Python-specific types without explicit support.

FastMCP could add that support. They could detect dataclass parameters and auto-reconstruct them from incoming JSON. But that would be Python-specific magic that doesn't align with the language-agnostic MCP protocol.

Instead, they chose to stay close to the protocol: JSON-compatible inputs, automatic serialization of outputs. It's a reasonable design decision once you understand it.

The trap is that it's not obvious until you deploy.

My Admittedly Biased Conclusion

If you're using FastMCP:

- Only use primitives as tool parameters (str, int, bool, list, dict)

- Use dataclasses freely as return types (FastMCP handles serialization)

- Construct complex types internally (parse primitives into dataclasses inside your function)

- Write integration tests that invoke through the actual MCP protocol (see: [Why Your Tests Passed But Your API Failed](../Post 1 of 4 - Why Your Tests Passed But Your API Failed - The SerDe Boundary Problem.md))

This pattern works beautifully. Your API is clear, your types are documented, your tests pass and work in production, and you're working with the framework instead of against it.

Just don't assume that because dataclass outputs work, dataclass inputs will too. That asymmetry is the trap, and now you know where it is.

Related Posts

- Why Your Tests Passed But Your API Failed: The SerDe Boundary Problem - The testing gap that hid this bug

- Code Review in the Age of AI - How AI almost made it worse

- Debugging False Memories - A case study in systematic investigations

No comments:

Post a Comment